A Guide to the Maqam Tuning Presets for Ableton Live 12

By Sami Abu ShumaysThese new maqamMaqam (pl. maqamat) is the modal melodic system used in the Arab world. "A maqam" refers to one of the modes used with a particular scale and melodic vocabulary and set of expected modulations.Visit the link to learn more presets I designed for Live 12 are unique in the world of digital maqam instruments. In providing these presets, my role is equivalent to that of a maker building musical instruments used to play maqamat. The materials from which any instrument is built, its design and construction, limit and shape the music it can be used to create; that is as true of any digital instrument as it is of one made from wood or skin or metal.

Maqam music is spread from North Africa all the way through Central Asia into Western China, with broad regional distinctions and even finer distinctions from country to country and city to city. The presets for Live 12 are based on maqamat specifically from the region of Egypt and greater Syria, a region with shared repertory and style; this is also the region of my own musical practice, and it is on the basis of that practice that I offer them.

For the purposes of the rest of this guide, I use the word “maqam” to refer to “the maqam system of Egypt and Greater Syria.”

Defined simply, a maqam is a musical mode that includes both specific scale tuning and specific melodic vocabulary and patterns of modulationIn Arabic music, the act of moving to a new jins or maqam.Visit the link to learn more. A maqam is not a scale, but it has a scale. The presets include various possible tuning options for several common maqam scales.

In this guide you will learn:

- the basics of how to use the presets to play maqam-based music

- the limitations of the presets in enabling the full range of possibilities within the maqam system

- the rationale for the tuning choices given, and the process through which they were developed

- suggestions for how to use the different tuning options, including for the purpose of ear-training

I am going to start by describing how to use these presets to play maqam-based music in an idiomatic way – including how professional Arab musicians might want to approach them, as well as any students and lovers of maqam-based music. Of course, the presets can be used by anyone in any way you wish (it's your instrument now, if you have Live 12) - my description below of how to use them for the maqam is merely intended as guidance.

Let’s begin by looking at the preset named “Rast 1 - Egypt mid 20th.ascl”. The 12 keys of the standard keyboard are assigned to pitches named:

The first thing to notice is the substitution of something called “E1/2♭” (“E-half-flat”) for E natural, and “B1/2♭” (“B-half-flat”) for B natural. The scale for Maqam Rast in the key of C, as described in traditional maqam theory, can be written as follows:

So, on the most basic level, if you play a C major scale on your keyboard using this preset, you’ll hear a scale usable for Maqam Rast on C (keep in mind that doesn’t mean that simply by using this scale you would be playing Maqam Rast – any more than using the C Minor scale would mean you are playing Maqam Nahawand – because the identity of the maqam is rooted in the melodic vocabulary it uses, not simply the scale).

Modulation

Maqam-based music, like Western music, makes frequent modulations, many of which use alternate pitches for different scale degrees, and/or change the key of the tonic. Understanding the basic structure of these modulations is key to knowing how and when to use the other notes provided, as well as what is and isn't possible using this preset.

Arabic melodies are rooted in vocal practice, and melodies tend to move in a stepwise manner, with few of the larger jumps and arpeggios typical of Western melodies. It is typical for Arabic melodies to use a narrow range of a few notes for a while, before moving on to another range of notes, rather than using the whole scale all at once. This way of moving melodically is the basis for maqam theory and practice, especially the movement from jins to jins.

The basic building block of a maqam is called a jinsJins (pl. ajnas): a scale fragment of 3, 4, or 5 notes with a specific mood and melodic vocabulary.Visit the link to learn more. A jins (plural ajnas) is a melodic entity that uses a fragment of the full scale of the maqam – 3 or 4 or 5 notes – and has a specific tonicization, along with its own melodic vocabulary and mood (See http://maqamworld.com/en/jins.php and chapter 13 of Inside Arabic Music). The maqam is made up of movements among different ajnas.

A typical song or improvisation in Maqam Rast might begin in Jins Rast, which uses the first five notes of the scale:

Jins Rast has its own particular melodic vocabulary using these notes (a subject I teach in the online lessons I developed), and within the jins there is typically a move from emphasis on the tonicThe tonic is the "home note" of a scale or of a piece of music that's in a key, or a note of resolution in modal music.Visit the link to learn more (the C in this case) to what is called the ghammazA note of secondary melodic emphasis within a maqam that can also become a new tonic in modulation to new ajnas.Visit the link to learn more - a note of secondary emphasis, which can also become a new tonic - in this case, the G (in the case of Jins Rast this secondary tonic is always the fifth scale degree above its tonic).

After some time spent in Jins Rast, the melodies might tonicize the G by moving to Jins Hijaz on G, which uses 4 notes at the top of the scale:

The melody might move from there to Jins Nahawand on G:

and back to Rast on C. Or it might move next to Jins Upper Rast on G:

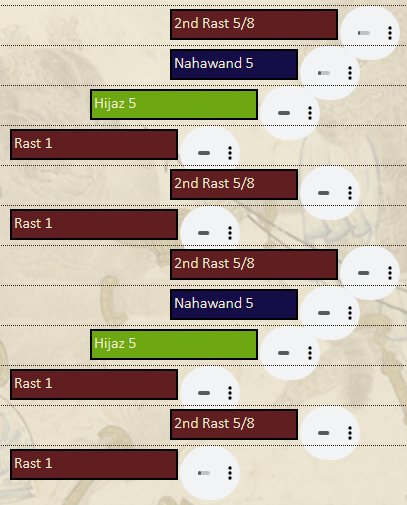

There’s no particular required order for these modulations; in fact they occur in numerous different orders in the repertory. If we imagine each jins as a colored box, an analysis of the popular Muwashshah “Ya Shadi il Alhan” looks like this:

[this image comes from my website "Maqam Lessons"]

The numbers next to each jins name refer to the scale degree of the jins tonic relative to the tonic of the maqam. Here is a similar analysis of part of another song in Maqam Rast, "Hayrana Leh":

Modulations to other ajnas are possible, but the number is not unlimited. Every maqam has a finite number of jins modulations that listeners and musicians expect. These expectations are built from repeated listening, memory, and muscle memory, and they are part of the essential structure of each maqam. They can be changed over time, like any cultural product – which is to say that there’s no deterministic reason that modulations must occur in this way, they are merely habits. These modulations are arbitrary – which means they must be learned one-by-one on their own terms, rather than arising because of some simple set of rules about modulations.

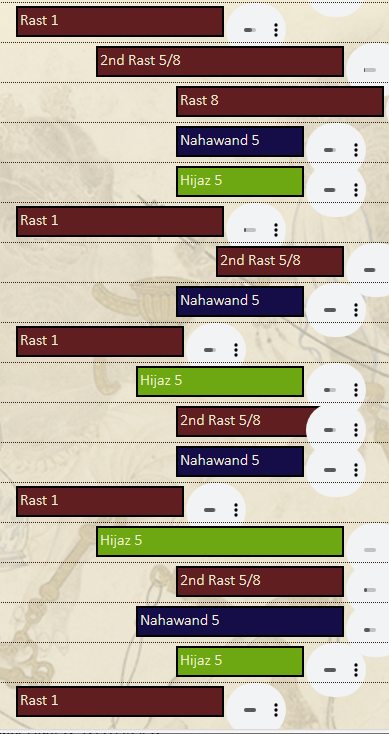

Based on the possibilities demonstrated in the repertory we can create a network diagram for Maqam Rast that looks like this:

The lines refer to possible modulations from jins to jins within the network. What this means in practical terms is that a musician playing in Maqam Rast, whether it’s a song or improvisation, would typically make a number of these moves, and would like to have all of them available.

The design of traditional Arabic instruments allows for this variety, which arises out of the possibilities of the voice (as I’ll describe below in the discussion on tuning). The oud and violin are both fretless string instruments that enable continuous pitch variation like the voice. The qanun, a type of lap harp, has strings tuned in courses of 3, with 7 notes per octave; each course of strings has anywhere from 5-17 metal tuning levers (called ‘urab in Arabic and mandals in Turkish) that enable microtonal pitch variation – so, for example, the ‘urab on the E string would enable multiple E-flats, multiple E-half-flats, and multiple E-naturals. The skill in qanun playing is in anticipating the jins modulations and flipping the levers to change pitch, while simultaneously playing the melody with the other hand.

So what does the design of the preset named “Rast 1” enable, with these 12 pitches?

We’ve included those possibilities in the text of the preset itself, where you will see the following list:

! Jins modulations possible within this pitch set:

! Rast C: C D E1/2♭ F G

! Nahawand C: C D E♭ F G

! Nikriz C: C D E♭ F♯ G

! Sikah E1/2♭: E1/2♭ F G A♭

! Nahawand G: G A B♭ C

! Upper Rast G: G A B1/2♭ C

! Hijaz G: G A♭ B (missing, but could fake with the B1/2♭) C D E♭

! Saba Dalanshin A: A B1/2♭ C D♭

Let’s look more closely at Hijaz G. In the list it’s written:

! Hijaz G: G A♭ B (missing, but could fake with the B1/2♭) C D E♭

Rather than:

! Hijaz G: G A♭ B C D E♭

That’s because in this preset we don’t have a B natural – we gave it up in order to create the possibility of a B1/2♭. In order to accommodate everything we need for Maqam Rast, we’d need three kinds of B: B♭, B1/2♭, and B♮. Since we don’t have the B♮, we can compromise by using the B1/2♭ for Jins Hijaz. It doesn’t sound quite right, but it will do. Nonetheless, the A♭ provided in this preset is very nice for Hijaz (a little higher than equal-tempered), and in fact a lot of melodies in Maqam Rast will only briefly touch on Hijaz, sometimes only using that A♭, so it’s not a total loss.

This illustrates the type of compromises required to accommodate the maqam system to a 12-note keyboard. In order to work around this limitation, we* took the following approach:

- Design multiple presets for each maqam provided, to enable all of the modulations expected within the maqam

- Provide multiple presets using only 12 pitches, in order to enable playability on a standard keyboard – this is a must for any professional Arab keyboard players * wanting to use these presets, who are already used to "Oriental" keyboards that allow the modification of some notes to quarter-tones on a standard keyboard

- Provide a preset for each maqam that includes all of the modulation possibilities, and therefore contains more than 12 pitches. This is great for those wishing to create music with all of those variations in only one preset, but it doesn’t map to the standard 12-note keyboard, so it will take some getting used to for keyboard players.

* ("we" here means myself, Sami Abu Shumays, and Dennis DeSantis of Ableton: the two of us worked very closely together in designing the whole approach of these presets in a way that would be valuable to Ableton users of different kinds.)

Let’s look at a few more of the presets we provided for Maqam Rast.

The file named "Rast 2 (Suznak) Egypt Mid 20th.ascl" has the following set of pitches:

! @ABL NOTE_NAMES C D♭ D E♭ E1/2♭ F F♯ G A♭ A1/2♭ B♭ B♮/C♭

which enables:

! Jins modulations possible within this pitch set: ! Rast C: C D E1/2♭ F G ! Nahawand C: C D E♭ F G ! Nikriz C: C D E♭ F♯ G ! Sikah E1/2♭: (D♯) E1/2♭ F G A♭ ! Hijaz G: G A♭ B♮ C D E♭ ! Bayati G: G A1/2♭ B♭ C D E♭ ! Saba G: G A1/2♭ B♭ C♭ D E♭ ! Hijazkar G: E♭ F♯ G A♭ B♮

In comparing it with “Rast 1,” note the following differences and similarities:

- Both of these presets give up E♮ in favor of E1/2♭

- Rast 2 gives up A♮ in favor of A1/2♭, unlike Rast 1

- Rast 2 does not give up B♮, and has no B1/2♭

The consequences in terms of possible jins modulations are as follows:

- Upper Rast G and Nahawand G are not possible in Rast 2, as both require an A♮ (and Upper Rast requires both the A♮ and B1/2♭)

- Because of the inclusion of A1/2♭ and B♮ several other ajnas are available, including a good Hijaz on G, as well as Bayati, Saba, and Hijazkar on G.

Thus by using both presets in tandem, you could play nearly all of the most common jins modulations possible for Maqam Rast. Before looking at the Rast presets that include more than 12 pitches, it’s worth pausing for a moment and comparing these two presets to the design of the Arabic accordion, the first keyboard instrument used in traditional Arabic music.

The accordion was introduced to Arabic Music at some point in the early 20th century, and is often associated with Alexandria in Egypt, where there was a large population of European expatriates, especially Greeks and Italians, in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The solution to accommodate the maqam to the accordion is similar to what we’ve just seen in these presets: some of the accordion reeds were shaved so that an E1/2♭ could be substituted for E♮ and a B1/2♭ for B♮ – since the accordion, like other keyboard instruments, enables only 12 pitches per octave. Another ingenious solution was developed, enabling greater flexibility: because some accordions have a different set of reeds that play when the bellows is compressed vs. when it is expanded, the E1/2♭ could be used in one direction and the E♮ in another. Thus Arabic accordions frequently became 15-pitch instruments despite using a 12-note keyboard, pairing E1/2♭ and E♮ on one key, B1/2♭ and B♮, and A1/2♭ and A♮. Other common substitutions/pairings enable the use of F1/2♯ and C1/2♯.

This design for the Arabic Accordion is still in use to this day (a maker will take a good German or Italian accordion and modify it), and is the basis for Arabic Keyboard design starting in the mid-20th century. Contemporary “oriental” synthesizers are rooted in this approach, enabling the substitution of quarter-tone notes for standard pitches in the scale with the touch of a button (this in fact comes close to the way the qanun is played, with pitch changes happening on various scale degrees in the course of performance). It is worth noting that in all these cases the result is an equal-tempered instrument, producing maqam scales based in 24EDO – an issue we’ll discuss in the next section.

While the use of a 12-pitch keyboard requires compromises within the maqam system, Ableton Scala files enable the creation of sets of greater than 12 pitches. Let’s look at the file named “Rast 5 - all the modulations.ascl”. This preset is a 15-pitch set using the following notes:

! @ABL NOTE_NAMES C D♭ D E♭ E1/2♭ E F F♯ G A♭ A1/2♭ A B♭ B1/2♭ B♮/C♭

We have all three choices for varieties of E, B, and A: the flat, half-flat, and natural versions. The result is that we can produce the following ajnas using this preset:

! Jins modulations possible within this pitch set: ! Rast C: C D E1/2♭ F G ! Nahawand C: C D E♭ F G ! Nikriz C: C D E♭ F♯ G ! Sikah E1/2♭: (D♯) E1/2♭ F G ! Nahawand G: G A B♭ C ! Upper Rast G: G A B1/2♭ C ! Hijaz G: G A♭ B♮ C D E♭ ! Bayati G: G A1/2♭ B♭ C D E♭ ! Saba G: G A1/2♭ B♭ C♭ D E♭ ! Hijazkar G: E♭ F♯ G A♭ B♮ ! Saba Dalanshin A: A B1/2♭ C D♭ E♮ F ! Jiharkah C: B1/2♭ C D E♮ F

The inclusion of an E♮ allows for Jins Jiharkah C, which we couldn’t get in either of the Rast presets discussed above, as well as a fuller version of Jins Saba Dalanshin A. These two rarer modulations in Maqam Rast are nonetheless still idiomatic and essential.

In short, with this preset an experienced Arab musician will be able to play all the ajnas typically expected as modulations within Rast, therefore all of the songs and pieces in Maqam Rast from the repertory. However, as noted above, because this preset – like all Ableton Scala files – maps each note to a different key on the keyboard, it may create cognitive dissonance for Arab keyboard players (or frankly, anyone who is a live performer on keyboard in other genres) because pitches aren’t mapped to the keys one would expect.

This approach – accommodating the maqam system to the Ableton Scala file through the use of multiple presets for each maqam, including some that use 12 pitches and some with more than 12 pitches – is duplicated with the other major maqamat playable from this batch of presets:

- Maqam Bayati

- Maqam Saba

- Maqam Hijaz

In total, the full set of maqam presets I designed for Live 12 enables the performance of nearly all maqam-based music from the region of Egypt and the Levant (for the sake of reference we can call this “Sharqi” music; Sharqi means “Eastern” and is originally a term adopted in response to European descriptions of the Arab world as “The East,” in contrast with “Gharbi” – “Western” music). Although that list of maqamat is smaller than the full list of maqamat you might see in a textbook, if you look more closely at the list of ajnas possible within each preset, you will find that they enable all of the “family” members of each maqam named – which in traditional maqam theory means those maqamat with the same bottom jins, but using different ajnas at the top of the scale.

I haven’t provided presets for the maqamat Nahawand, Kurd, or Ajam, which use the minor, Phrygian, and major scales respectively, and which can be played on a standard keyboard (although versions of those maqamat are also playable within the presets provided for Rast and Hijaz and Bayati). Maqamat of the Sikah family are also playable using the Maqam Rast and Maqam Hijaz presets (but I’m going to have to have a more extended exploration on how best to provide a dedicated preset for maqamat whose first note is a quarter-tone relative to the standard keyboard).

Several things can help you use these presets to play all of the common maqamat used in Sharqi music:

- Knowledge of how the maqam system works, which can best be gained through practice

- the explanatory text provided in the Ableton Scala files, especially the list of jins modulations

- The individual maqam preset pages on this website, which go into more detail and also include playable features

- The book Inside Arabic Music, which provides detail on all the ajnas (Chapters 13-16), and network diagrams showing the modulations used by all of the maqamat (Chapter 24)

- The websites Maqam World (which includes scales for the maqamat as well as musical examples) and Maqam Lessons (which has jins-by-jins analyses of songs)

Tuning

What makes these Ableton Live presets unique in the world of digital maqam instruments is the way they incorporate tuning variation.

I’d like to start by clearing up some misconceptions about the tuning of musical scales. The first melodic instrument is the voice, a continuous-pitch instrument. When ethnomusicologists study melodies and musical scales from around the world, they discover infinite variations in tuning, and intervals of arbitrary sizes. Yet music theorists and tuning experts continue to believe – mistakenly – that the tuning of musical scales is determined by mathematical principles. Indeed they can be, but that is only one case among many; the act of determining tuning through mathematical operations limits the range of possibilities available to music, and musicians have gone way beyond those limitations throughout history.

Tuning theorists resist natural variation: they attempt to fight back against the human tendency to change and vary cultural objects, and they have done so since the time of Plato and Pythagoras – by attempting to standardize scales and provide rules for their construction. Plato’s discussion of musical scales in The Republic – wishing to prohibit the use of scales other than the Dorian and Phrygian, to prohibit “multiplicity of strings,” “panharmonic scales,” and “artificers of lyres with three corners and complex scales, or the makers of any other many-stringed, curiously harmonized instruments” – shows this dynamic from its inception. The practice of music has always been too messy for music theorists.

Attempts to standardize Arabic scales date back to the introduction of the 24EDO scale beginning in the 19th century; run through the 1932 international conference on Arabic music, where an attempt was made to eliminate cultural variation in maqam scales; to the present, when every tuning expert on the internet has their pet theory about how maqam scales should be tuned, invoking higher and higher partials in the harmonic series or greater and greater numbers of equal divisions of the octave.

The question of what would be most suitable for these maqam presets faces a fundamental contradiction: on the one hand, the fact that the vast majority of keyboard instruments used in Arabic music have been tuned in 24EDO, and contemporary keyboard players are used to that tuning; and on the other hand, the fact that the tuning used by traditional acoustic instruments is not based in 24EDO and exhibits considerable variation.

Our decision was to include both, which is also a practical concern – because we expect people to use Live 12 in a variety of contexts, with a variety of other instruments in ensembles. Including the 24EDO versions, which will satisfy the needs of many practicing keyboard players, gave us the freedom to design the non-EDO versions in ways that expand the palette of tuning possibilities.

The non-EDO maqam presets capture some of the natural variation that results in many differently-tuned variants of the same conceptual maqam scales, and are rooted in the knowledge of arbitrary tuning practices gained through oral tradition. Understanding these cultural and practical tuning principles will help you understand the tuning choices reflected in these presets, and when to use them.

Maqam scales have an incredible degree of tuning variation. This variation is a crucial feature of the music, and it is salient to listeners, who can identify music by its maqam-tuning “accent.” Recent studies have shown that even non-musician listeners to maqam-based music have a much higher degree of pitch sensitivity than those who don’t listen to maqam-based music. It is perhaps partly for that reason that Westerners, for whom the level of tuning variation isn’t audibly salient, have often tried to standardize Arabic scales, thereby quashing the variation culturally inherent in the music.

We opened this essay by observing that the physical features of instruments result in inherent musical limitations. To understand the tuning variation within maqam, we explore the capabilities and limitations of the instrument it is rooted in: the human voice. Maqam is first and foremost a vocal phenomenon; although musical instruments are obviously a large part of maqam traditions, the voice has dominated the music throughout its history.

A major vehicle for maqam in the region has been the practice of Qur'anic recitation. For 14 centuries, reciters of the Qur'an have sung the words to a capella improvisation in maqam. Over its history, maqam has drawn from melodic influences across the region (ranging from Ancient Egypt and Babylon, Ancient Greece, Rome, Iran, the Byzantine Empire, Africa, Mongolian and Turkish invaders, and Europe) and is practiced in both secular and sacred contexts (Islamic, Jewish and Christian religious music and chant). Qur’anic recitation has long been a repository of all of these influences, and in turn a major influence on the other musical practices of the region. Just one example: Umm Kulthum, the most important Arab singer in the 20th century (and the second-most-recorded artist in the history of music, after Indian playback singer Lata Magneshkar), and one of the pillars of the Sharqi maqam tradition, was the daughter of a Sheikh (someone who has memorized the Qur’an); she herself memorized the Qur’an, learning maqam through its recitation as a child, before embarking on a career in secular music in Egypt.

The human voice is the first melodic instrument; recent evidence shows that singing even predates language in human evolution. The voice has the ability to produce, within its range, an infinite spectrum of pitch and of timbres, consonant and vowel sounds; the ability to imitate and copy any other sound heard within the frequency range of human hearing. This range of possibilities allows for the selection of an infinite number of sets of distinct auditory symbols, which social groups use to differentiate their cultures, languages, and music practices from each other. Just as a particular accent or style of cooking lets you know where a person is from, music is not supposed to sound the same from village to village, and the voice’s infinite flexibility facilitates cultural differentiation.

There is no particular reason for the voice’s use of pitch and melody to follow the harmonic series, even when voices sing different pitches together (itself a particular, not universal, cultural choice), any more than there is any particular reason for vowel sounds to maximize only one upper partial rather than blending them. The physical realities of resonance provide only the broadest set of limitations, but it is the act of choice within those limitations that results in pitches for use in musical scales. If in your village, you like a third scale degree in your scale that happens to be a just major third above your first scale degree, then I’m just as likely to make my third scale degree slightly higher or lower than yours, to distinguish myself and my village. Scales are truly arbitrary, not determined by mathematical laws or operations. The constraints and motivations for pitch choices, on the contrary, are entirely cultural: memory and cohesion within the social group, differentiation outside of the group. (See chapter 11 of Inside Arabic Music.)

This context of arbitrary cultural selection enables us to understand the dizzying array of scale tuning possibilities within the maqam system. As an Arabic violinist and vocalist I use at least 12 distinct pitches within the span of a semitone within various different maqam scales. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, there’s no way for just intonation/rational relationships within the harmonic series to be the determining factor for the selection of that many distinct pitches, for reasons of perceptual salience: low partials like 3 and 5 stand out from the background, but a relationship like 27/22 (one of the earliest mathematical descriptions of the “neutral” third, given by the Andalusian Arab theorist Zalzal in the 8th century A.D.) is no more perceptually salient, nor easier to produce by the voice, than relationships higher or lower than it by within 30-40 cents (until you hit 5/4 and 6/5 on either side). At that level of granularity, the salient factors for pitch selection are: 1. the “Just Noticeable Difference” (JND) - by how many cents can the human ear tell pitches apart? - and 2. the muscle memory needed to reproduce distinct pitches with the required degree of precision.

Added to the complexity of scale and pitch possibilities within one maqam practice is the fact of regional and historical variation of pitch across closely related practices. We can illustrate this with the basic scale for Maqam Rast, which as we saw above can be written as follows:

This scale is used in Arabic music from North Africa through the Levant, Iraq, and the Arab Gulf; yet across that wide geography the pitch of the third scale degree – the E “half flat” – varies slightly from region to region. Within my own particular region of practice, it is typically slightly higher in Syria than it is in Egypt. In addition, evidence from music recordings made in Egypt from the early 20th to the early 21st century shows that the pitch of the E “half flat” got lower over the course of the 20th century. (I put E "half flat" in quotes here because it is a pitch roughly, but not exactly, in between an E natural and an E flat – but it is treated conceptually as a quarter-tone note.)

The fundamental question to ask is: when the tuning of the scale changes in this way, does the maqam change? The answer is no. Maqam Rast as played by a Syrian musician is intelligible to an Egyptian musician as the same maqam. A late 20th century or early 21st century Egyptian musician performing an early 20th century Egyptian song in Maqam Rast will play the song with their current intonation, and it will still be perceived as the same song. It’s no different than if you were to play a song you know on an out of tune piano or guitar: you’d still recognize the song, though you’d also probably recognize that the tuning is a little off (how much, depending on your pitch sensitivity and training). Thus we can say that what provides the essential coherence of maqam is melody more than pitch precision. (It’s also for that reason that we can’t identify Maqam Nahawand with the minor scale, even though it uses the same pitches, as I noted earlier).

This regional and historical tuning variation in the maqamat functions in the same way that accents do in spoken language – it identifies the musician by which region he or she comes from. Experienced listeners can tell whether a musician is from Egypt or Syria or Iraq, based on the tuning of their Rast scale, just as native speakers of English can tell whether another speaker is from Ireland or Australia or Boston by their accent. Variation in pitch is equivalent to variation in vowel sounds; it changes the absolute sound, but preserves the identity of the melodies.

In order to accommodate this tuning variety, I’ve provided multiple tuning presets for Maqam Rast: a version with a very high E1/2♭ suitable for Syrian music (“Rast 3 - Syrian mid-20th.ascl)"; one in the middle for mid-20th century Egyptian music (“Rast 2 (Suznak) Egypt Mid 20th.ascl)"; one rather low for later 20th century Egyptian music (“Rast 1 - Egypt mid 20th.ascl)". How I selected the exact pitch values for use in these presets I’ll discuss in more detail below. Also, as noted above, I provided several 24EDO versions of Rast.

If the voice has an infinite spectrum of tuning possibilities, and maqam is rooted in a capella singing practices, then shouldn’t we expect even more variety in maqam tuning than we ordinarily see? Even more than described above? In fact there is a great deal more variety in the tuning of Qur'anic recitation and the call to prayer than in mainstream urban/ secular/ instrumental maqam practice, for exactly that reason. It is not uncommon to find melodies for the call to prayer that have no just or equal-tempered intervals; a common melody in a maqam called “Hijaz Gharib” has a fourthPitches a fourth apart have a 3:4 frequency ratio (in just intonation) or a difference of 500 cents (in 12 tone equal temperament).Visit the link to learn more that is noticeably flatter than just intonation, and the second and third of the scale are also “off” what might be expected. One can hear similar variation especially in isolated rural traditions in the Middle East.

On the other hand, mainstream maqam practice also has a long history of being intertwined with the creation and playing of musical instruments. In comparison with the range of the human voice in terms of timbre, pitch, and other dimensions of sound, every musical instrument we’ve ever created is deeply impoverished. Yet because selections must be made from that infinitely-possible vocal variation in order to construct a coherent musical vocabulary, those vocal selections tend to align with the possibilities of the musical instruments used in any particular cultural group, mutually shaping each other over time.

In the construction of musical scales, physical instruments have provided particular limitations depending on their material: columns of air running through tubes, animal skin stretched over wooden frames, strings of fiber or metal pulled to tension, all with their distinct physical resonance qualities. The history of string instruments tuned in just intervals dates back at least 4,000 years to the ancient Near East, Ancient Egypt and Babylon in particular, from which Pythagoras and the Greeks learned.

As a result of the prevalence of multiple-string instruments, the use of just fourths and fifthsPitches a fifth apart have a 2:3 frequency ratio (in just intonation) or a difference of 700 cents (in 12 tone equal temperament).Visit the link to learn more to define musical scales has been a feature of musical traditions around the Mediterranean for this entire period. The Ancient Greeks defined the “Tetrachord Genus” using the interval of the just fourth, with different possible intervals within it – and the medieval Arabs adopted this model, Arabizing the Greek word “genus” into “jins.” The oud, itself tuned in just fourths, became the model used to define and illustrate the jins and the maqam.

The result is that maqam scales have a hybrid intonation model: the majority of the intervals in the scale are tuned according to Pythagorean intonationPythagorean tuning is an approach to tuning based on stacking pure fifths (i.e. fifths with an exact frequency ratio of 2:3).Visit the link to learn more (just fourths and fifths), while certain other intervals are tuned in ways that are harder to define, and which have varied culturally. In the case of the Maqam Rast scale –

– the C, D, F, G, and A are all open strings of the oud, and therefore tuned in just fourths and fifths (A-D-G-C-F); while the E1/2♭ and B1/2♭ are both fingered and culturally variable.

For Jins Hijaz, for example:

The G and C are tuned as a just fourth, but both the A♭ and B♮ are culturally variable (the A♭ tends to be higher than an equal-tempered or just A♭, and the B♮ tends to be lower than an equal-tempered or just B♮)

In the case of Maqam Bayati:

The D, F, G, C, and A are tuned in just fourths, although sometimes the A leans a little higher; the B♭ is often Pythagorean (a just fourth above F), but is sometimes a little lower than that (especially in Lebanese folk music). The E1/2♭ in Bayati tends to be lower than the E1/2♭ in Rast, and is also culturally variable.

There are too many examples for me to list out here, and in any case, such a list would be useless. Each of these pitch variants has been transmitted by ear and must be learned by ear, one by one, on their own terms. It may seem like a daunting exercise, except when you realize that you learned all the same type of information, without thinking about it, about the many different vowel sounds and shades of those sounds in the language you speak. If you’re a native speaker of English, you know that there are many different “a” sounds, as in “father” vs. “cat” vs. “car” vs. “can.” You also know that you can’t learn those vowel sounds easily in isolation from words, and you might suspect that there is even more variation than is defined in phonics books.

The same is true of the intonation of different intervals in maqam – they can be learned easily by children through the process of imitating melodies and learning songs by ear – but defining them has presented a challenge for music theorists mistakenly believing that there has to be a mathematical rationale for them. And accounting for all of them presents a practical challenge that is solved by treating them in broad categories – “flat” (although there are multiple shades of flat), “half-flat” (multiple shades), “natural” (multiple shades).

I learned all of these intonations by ear over the course of two and a half decades of playing the violin and singing – two instruments that enable continuous pitch variation, and require the development of a sensitive ear and muscle control to produce precise pitches. This may come out like a humblebrag, but I mention my own pitch sensitivity in this context because it is relevant to how I developed the presets: also by ear.

In 2010, the Peterson Tuning company hired me to help them create a Maqam Rast scale for one of their tuners, which they did by taking me into a recording studio and measuring my playing on the violin. I repeated the scales many times, playing melodies in the maqam and going back to long notes, playing scale fragments, etc. I learned two important things from that session. First, that my pitch precision on the violin is within a range of 2 cents or less – meaning that every time I played a particular note over the course of two hours, the variation was within that narrow range. Second, they noticed that I used two different A naturals, around 7 or 8 cents apart (but again, with precise clusters around those pitches), depending on particular melodic patterns.

My pitch precision is not exceptional for Arab musicians, it is average – one might say expected of any professional-level violin player, oud player, or singer, because Arab music listeners are sensitive to what they call “nashaz” – being out of tune. You might say that over the course of my musical education and career I have built myself into an instrument to deliver maqam.

The process of developing the non-EDO presets for Ableton required that I translate this aural knowledge into Scala files, with absolute cent values for the various pitches of maqam scales; that process of translation itself influenced the values I provided for the pitches.

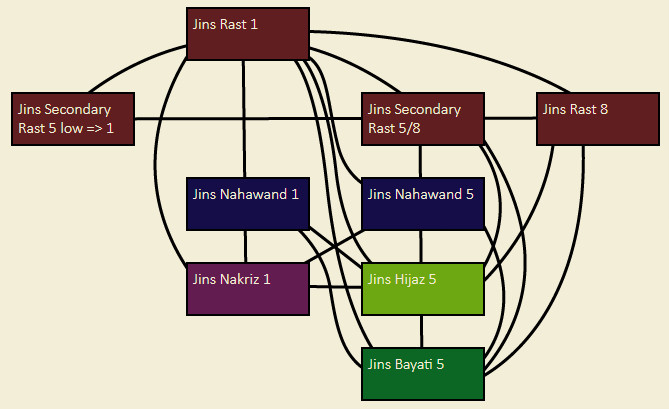

I did not use a measuring device, neither to measure my own playing, nor to measure the pitch of popular songs in each maqam. Instead, I used a musical instrument that I could adjust and play with: alt-tuner. Alt-Tuner is a DAW plugin that works in Reaper to retune MIDI data, to create alternate tunings for keyboard instruments. It is especially designed to accommodate the many different varieties of just, mean-tone, and tempered tunings that developed in the West over the last several centuries. Its interface is incredibly flexible and allows for two crucial things: 1. The possibility of flipping between multiple pitches on the same key – like a qanun! – and 2. the ability to retune any of the pitches cent-by-cent.

I started experimenting with alt-tuner a little over 5 years ago, in the fall of 2018. The most important thing I learned from this extensive period of experimentation is that I have no single master version of any maqam in my ears. Every time I sit down with alt-tuner I tweak previous scales, play some more music, and tweak some more.

Here are some key takeaways, framed specifically around Maqam Rast, which we’ve been focused on throughout this guide:

- Although I started with a Pythagorean frame (A-D-G-C-F-B♭-E♭ as just fourths) I discovered that I wanted to adjust some of those notes.

- For example, the B♭ in Rast (specifically the context of Jins Nahawand on G) is noticeably lower than Pythagorean in some of the music I play and enjoy – especially early 20th century repertory. The E♭ in Nahawand on C (one of the expected modulations) is also often lower than Pythagorean. Both of these reflected my aural intuition from the violin, but were confirmed by testing with alt-tuner.

- Sometimes I wanted the D and A to be higher than Pythagorean, by around 5-6 cents, yielding extra large major seconds. (One of the presets I offer here reflects that). This is also true in maqam Bayati, where the fifth above the tonic is often higher than Pythagorean. Again, testing with alt-tuner confirmed my aural intuition, and also gave me precise cent values.

- Depending on what piece from the repertory I played, I wanted the E1/2♭ to be higher or lower, as I expected.

- My intuition that the B1/2♭ in Rast is relatively higher than the E1/2♭ was confirmed. This held true even with different E1/2♭s

- Several half steps are quite large, for example the interval between G and A♭ in Jins Hijaz G, and between C and D♭ in Saba Dalanshin A; while other half steps are small, as between B♭ and C♭ in Saba G. Again, I knew this intuitively (It’s something we talk about explicitly as musicians), but it was interesting to confirm and measure it.

- Given the ability to toggle between multiple different versions of every conceptual pitch, I used them. My ears wanted more rather than less variability, especially in certain pitches.

- Yet I never wanted to change the tuning of the F or the G in Rast - which for me stayed in their Pythagorean positions no matter what other variability I played around with.

The challenge in developing the Ableton presets became how to reduce that complexity and variety to a smaller set of scales that would be widely useful. I did the following:

- I decided to focus on iconic repertory as a guide for my ear in developing the scales. What that means is that I’d adjust the scale to the version I thought I wanted, and then play the song using that scale, and then make further adjustments until I was satisfied. I’ve named some of those reference pieces in the Ableton Scala files, but that doesn’t mean that I guarantee that these scales accurately reflect the tuning of the master recordings of those pieces! It means that that’s the tuning I wanted to use to play those pieces, which I had previously learned years ago by ear on the violin and/or voice. It’s therefore how my ear hears those pieces.

- I would then test it with multiple different instrument sounds, because at that level of fine pitch discrimination (2 or 3 cents or less) timbre had a noticeable effect on the sound of the intervals.

- I noticed that the preset values of pitch options in alt-tuner predisposed my choices in certain ways. Meaning: alt-tuner is designed to provide just intonation schemes with complex upper partials. In generating additional pitches for the “tap notes” (the different pitches on the same key I could toggle among – in the alt-tuner image, those are the pitches in the same column, and using the touchscreen I can tap on them to select), the default was to create notes with just tuning along a particular “rung” (a circle of fifths using a particular upper partial). Therefore I was predisposed to make those choices by the instrument itself, and even though I had the ability to adjust any one of those by an arbitrary number of (whole) cents in either direction, I didn’t always do that. (Does this mean that all of the maqam intervals can be accounted for by just intonation and I didn’t realize it before? No, it means that the ear adjusts and accommodates, and if that is what is provided as an option, the ear will accept it.)

- I rounded everything to the nearest cent value even though it wasn’t necessary for the Scala files. That includes the “Pythagorean” pitches. A Pythagorean/Just 5th is at 701.96 cents, and instead I just used 702 cents for the G. Same with all of the other pitches that either came from a just intonation default in alt-tuner, or one that came from such a default but which I adjusted by some number of whole cents (in the alt-tuner image those appear with a light gray background on the cent value). I did this in part to counter the effect of the just intonation defaults in alt-tuner, partly to make a point about the lack of absolutes in tuning, partly to make a point about pitch perception (I barely notice the difference of 1 cent, let alone fractions of it), and partly to be a jerk: I really want you to understand that this is all arbitrary, so I made an arbitrary decision.

At this point it will be helpful to compare all of the presets in Maqam Rast to see the different cent values I provided for the various conceptual pitches:

| Pitch | Rast 1 | Rast 2 | Rast 3 | Rast 4 | Rast 5 | Rast 6 | Rast 24 | Suznak 24 | Rast Fam 24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D♭ | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||

| D♭ | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | |||

| D | 200 | 200 | 200 | ||||||

| D | 204 | 204 | 204 | 204 | 204 | ||||

| D | 209 | ||||||||

| E♭ | 291 | 291 | 291 | 291 | 291 | 291 | |||

| E♭ | 300 | 300 | 300 | ||||||

| E1/2♭ | 342 | 342 | |||||||

| E1/2♭ | 347 | ||||||||

| E1/2♭ | 350 | 350 | 350 | ||||||

| E1/2♭ | 351 | 351 | 351 | 351 | |||||

| E1/2♭ | 356 | 356 | |||||||

| E | 382 | 382 | |||||||

| E | 400 | ||||||||

| F | 498 | 498 | 498 | 498 | 498 | 498 | |||

| F | 500 | 500 | 500 | ||||||

| F♯ | 590 | 590 | 590 | 590 | 590 | 590 | |||

| F♯ | 600 | 600 | 600 | ||||||

| G | 700 | 700 | 700 | ||||||

| G | 702 | 702 | 702 | 702 | 702 | 702 | |||

| A♭ | 800 | 800 | 800 | ||||||

| A♭ | 825 | 825 | 825 | 825 | 825 | 825 | |||

| A1/2♭ | 840 | 840 | 840 | ||||||

| A1/2♭ | 850 | 850 | |||||||

| A | 900 | 900 | |||||||

| A | 906 | 906 | |||||||

| A | 911 | 911 | 911 | ||||||

| B♭ | 990 | 990 | 990 | ||||||

| B♭ | 996 | 996 | 996 | 996 | |||||

| B♭ | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | ||||||

| B1/2♭ | 1050 | 1050 | |||||||

| B1/2♭ | 1056 | 1056 | |||||||

| B1/2♭ | 1061 | 1061 | 1061 | 1061 | |||||

| B♮/C♭ | 1092 | 1092 | 1092 | ||||||

| B♮/C♭ | 1100 | 1100 |

I will let you draw your own conclusion from that comparison, but I want to re-emphasize that the values given are a reflection of my own personal knowledge, developed through the specific personal experiences that I have had, both in learning maqam and then in developing the presets. Why do I center myself in this explanation? I do so to hammer home the same points I’ve been making throughout this guide: that scale tuning is absolutely arbitrary, the result of choices made by individuals, and that the material constraints of instruments, processes, and communities influence those choices.

The relationship between the individual and the community is complex, and cultural choices display a spectrum of agreement, from the absolutely universal (what the entire community agrees upon) to the absolutely unique (what only one individual chooses). In the middle are things that sub-groups of varying sizes agree upon. To use a linguistic analogy for this spectrum:

Language Group > Language > Dialect > Idiolect > Individual

Is analogous to:

Global Maqam Practice > Arabic Maqam systems vs. Turkish vs. Persian vs. Central Asian > North Africa vs. Sharqi vs. Arab Gulf vs. Iraq > Syrian vs. Egyptian etc. > Aleppo vs. Damascus etc. > Mohamed Kheyri vs. Sabah Fakhri etc.

I’m neither Sabah Fakhri nor Mohamed Khayri, I’m Sami Abu Shumays, and the only thing I am capable of giving you is Sami Abu Shumays’s version of the maqam. Anyone who tells you any differently – who claims to be providing a universal version of any maqam’s tuning – is lying, or ignorant, or both (copying the values provided by some theorist in some book is simply perpetuating that theorist’s individual choices, or perpetuating that theorist’s ignorance).

The final thing I’d like to address is how to use these scale presets for traditional maqam performance and ear training (if that’s what you want to do with them). It’s really a one-word answer: repertory. The identity of each maqam is encoded in melodies, not simply scale tunings; and conversely, the learning of melodies by ear is the only ear training method that actually works to learn microtonal scale tunings (just like copying the words and sentences of native speakers of a language is the only way to learn to pronounce the vowel sounds of their particular dialect/accent correctly).

I recommend the following:

- Play Arabic music from Egypt and Syria using these presets, and see how they work. That applies especially to understanding when to use the “accidentals” provided in the presets for modulations.

- Sing along with your playing on the keyboard. Tuning your ear requires using your voice. Sing along with original recordings, learn songs by copying recordings or copying experienced musicians.

- Test to see which tunings of the scales you like, and which tunings match the repertory you’re playing. Noticing the discrepancies will be as informative as noticing the alignment.

- Modify the presets by a few cents here or there in order to test whether they match the repertory you are playing and listening to.

It’s worth reiterating that nothing written above is meant to prohibit or discourage you from using these presets in any way you please. This guide is simply meant to clarify how to use the presets to play maqam music, especially because those without experience in Arabic music or other maqam-based traditions have many misconceptions about maqam, and many people falsely assume that determining the tuning of a scale is enough information to play maqam.

Yet you now have a unique instrument in your hands, and you may wish to do something entirely different with it. If I was on a desert island and found a musical instrument washed up on shore, with no cultural context to guide me, I’d simply start playing with it. If the tuning were different than I was used to, I’d think that was really cool, I’d start to sing along, create different combinations, etc. What would come out of it would be my own music, and likely it would be very different from the music that its maker played.

I hope you can find joy and inspiration in playing this new instrument, however you use it.